|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jake Jacobson | profile | all galleries >> The War Lover, Movie and the plane B-17 >> The Story of the Filming of The War Lover | tree view | thumbnails | slideshow |

Filming The War LoverBy Aero Vintage Books http://www.aerovintage.com/warlover.htmThe Movie... In 1959, novelist John Hersey’s The War Lover was published, creating the story of a volatile B-17 combat pilot who enjoyed his job just a bit too much. The setting was a fictional B-17 bomb group operating from England with the Eighth Air Force. Columbia Studios adapted the book for the silver screen in 1961. The film was shot in England, arrangements having been made to utilize the Bovingdon airfield as the fictional bomb group’s base. A a number of British war films including 633 Squadron (1964) and Mosquito Squadron (1969), besides The War Lover, were filmed there.

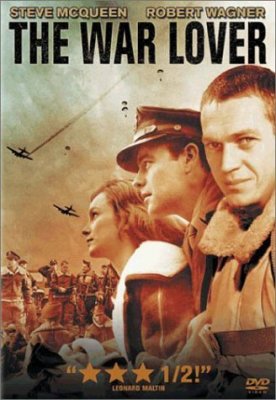

Two American film stars were signed, with Steve McQueen taking the title role as Capt. Buzz Rickson and Robert Wagner playing his stable copilot Lt. Ed Bolland. McQueen was perfect for the role, providing that dangerous rebel spark just beneath Rickson’s surface, while Wagner gave the copilot the even-handed, stable, but nonetheless heroic characteristics of the role. Columbia Studios turned to John Crewdson and his company, Film Aviation Services, to locate and operate the aircraft to be used in the film. They decided that three B-17s were needed to provide enough airfield and airborne activity to recreate the feel of bomb group operations. Crewdson was a colorful character, having cut his teeth flying gliders for the British Army, and then flew for a variety of operators around the world, including duty with the RAF in Britain. Crewdson had already made something of a name for himself amongst British filmmakers as he had provided helicopter services in a number of late 1950s film productions. He arranged for the Mosquitos used in 633 Squadron and also handled most of the aerial filming for the 1960s series of James Bond movies. But that was later. In the summer of 1961, he was out looking for three B-17s.

Crewdson knew that the Israeli Air Force had recently retired three B-17s and thought they might be available. However, he arrived in Israel about a year too late, as the airplanes had already been scrapped. He did, however, obtain the fuselage of one the Israeli airplanes for use as a studio prop. That airframe was B-17G s/n 44-83811. So, not finding what he wanted in Israel, he came to the U.S. confident he could locate his B-17s there. And, nosing around, he ended up at Ryan Field, located on the Arizona desert twenty miles west of Tucson. There, he found ex VB-17G s/n 44-83563 carrying the civil registration of N9563Z and owned by Aero American Corp. Aero American was a subsidiary of the American Compressed Steel Corp. of Cincinnati, Ohio, one of whose businesses was purchasing surplus airplanes from the U.S. military at nearby Davis-Monthan AFB. Aero American’s manager at Ryan Field was one Gregory Board, another colorful character who had flown Australian Buffalos in the early, dark days of World War II. Surviving that, he plowed through the post war years mostly on the murkier edge of aviation. John Crewdson immediately purchased the available B-17G on behalf of Columbia. Board, seeing a huge business opportunity, quickly flew Crewdson to Dallas to look over the half-dozen PB-1Ws owned by American Compressed Steel and stored there. Crewdson examined the sad airplanes and selected two airframes, N5229V (ex 44-83883) and N5232V (ex 44-83877) for purchase with the understanding that Board would quickly get them airworthy. The two PB-1Ws required much attention by the skilled hands of an Aero American crew to put them back into flying condition, but they were ready for flight by early September. Board and Crewdson delivered them to Ryan Field where they joined N9563Z.

Once the three B-17s were gathered, preparations were made ferry the airplanes across the North Atlantic to Bovingdon, delivery required by October 10 to meet the film schedule. Turrets and other wartime equipment was located at surplus yards around the U.S. and reinstalled to bring the aircraft back to the appearance of wartime Fortresses. Turrets were then removed and loaded as cargo for the ferry flight. Preparations completed, one silver and two Navy blue B-17s departed Tucson on September 17, with one B-17 commanded by Board, another by Crewdson, and the third by veteran pilot Don Hackett. Joining the crew for the transatlantic flight was author Martin Caidin flying as copilot on Board’s B-17. Caidin later produced the 1964 book Everything But the Flak about the ferry flight, an epic tale that certainly provides every detail of the saga, much of which was probably based on fact. The flight crews endured frustrating mechanical problems and terrible weather over the Atlantic, flying from Gander, Newfoundland, with a required diversion from Iceland into the Azores and then, eventually, Portugal. Nonetheless, the three B-17s processed through Gatwick on October 8, 1961, and then proceeded to Bovingdon in time to meet the film schedule. Crewdson and his crew went through the airplanes, reinstalling all the combat gear and repainting the aircraft in an AAF camouflage scheme with markings of the 324th Bomb Squadron of the 91st Bomb Group. A curious feature of the paint scheme of the bombers, though, was that the aircraft undersurfaces appeared to be painted either black or a very dark shade of grey.

The B-17 star of the film was The Body, but a wide variety of nose art, fuselage codes, and serial numbers were applied to all three B-17s to replicate a much larger number of aircraft. Careful editing and tight shots suggest a squadron of B-17s taxiing around Bovingdon in the operational scenes, but the wide shots indeed show only three aircraft. A close viewing of the taxiing aircraft, however, reveals the obviously patched paint and changed markings, but instead of being distracting it actually adds to the authentic nature of the film with the faded, worn, and patched finish of the airplanes. As a side note, none of the applied serials were applicable to B-17 production, another nit for the nitpickers but certainly not atypical of the times.

Operational scenes showing aircraft taxiing, taking off, and landing, plus scenes on the hardstands involving the principal actors were all filmed at Bovingdon. The distinctive control tower and other buildings are quite evident through those scenes. The Mantz crash landing from Twelve O'Clock High was inserted for one crucial scene and edited to blend with footage shot using the fuselage of the ex-Israeli B-17G. Tight camera shots don’t show that the bellied B-17 in the scene does not actually have any wings. The highlight of the film is the low level beat up of Bovingdon by Crewdson, flying solo, in a B-17. Beginning out of go-around maneuver from an aborted landing approach, low level in this case means the props ticking away a scant foot or two above the ground as the B-17 bears down on the airfield tower, and then banking between some hangars as it comes back around for another pass. As the low level bomber thunders across the field, a camera mounted in the bombardier position picks up a number of RAF aircraft parked near the tower, and a large RAF transport on a nearby taxiway, an indication that Bovingdon was, indeed, still active when the filming was underway. Principal filming at Bovingdon was completed in November, and then the aircraft were moved to Manston to film the over-channel scenes that brought the film to its conclusion. Manston, located on the east coast of England in Kent, had served as an RAF field during the war. Now the B-17s staged out of the field for the over water filming, and at least one B-17 was made to appear badly damaged with jammed bomb bay doors, one landing gear extended, and various holes shot through the fuselage and wings. Once airborne, at least one engine was shut down and feathered, and smoke rigged to emanate from the engine. While filming from another B-17, a crew of parachutists jumped from the damaged B-17 to simulate a crew bailout, a process that resulted in the fatality of one of the jumpers when he later drowned in the Channel. All the location filming was concluded by December 1961, and the production moved to film studios at Shepperton, near London. There, interior shots utilizing the Israeli B-17 were filmed, including process shots of McQueen and Wagner in the cockpit. The other less interesting non-aviation scenes were also completed at the studio and on location at Cambridge. After the editing and production was completed, the film was released in October 1962. Anecdotal John Crewdson, who operated the three B-17s for the film, was killed on June 15,1982, in a helicopter accident during movie filming. He was well known for his work in British films, particularly James Bond films, between 1956 and his untimely death. Greg Board, who rebuilt the three B-17s used in the movie from his Tucson, Arizona, base, fled the U.S. in September 1965 just ahead of authorities who sought him for alleged illegal export of Douglas B-26s for Portugal. He reportedly ended up back in his native country of Australia as an aircraft broker and may still be around. Martin Caidin, the prolific aviation and otherwise author who wrote the well-known account Everything But The Flak about preparing and delivering the B-17s, died in March 1997 of cancer. The two PB-1Ws, N5229V and N5232V, were scrapped, probably at Manston, shortly after the fliming was completed. The fuselage studio prop, 44-83811, apparently was stored at Croydon Airport (UK) for several years but was subsequently scapped. B-17G 44-83563 (N9563Z) went on to a long utilization as an air tanker, appeared in Tora! Tora! Tora!, and then to the National Warplane Museum. It still flies from Orange County Airport in Southern California, owned and operated by Bill Lyon's Martin Aviation. The film was done in black and white primarily to allow matching the footage used in Twelve O'Clock High and avoid color tint problems of footage from the wartime Memphis Belle. 91st BG markings were thus utilized to match both films. From Dik Shepherd: the actor who played ball turret gunner Junior Sailen was Michael Crawford who went on to a distinguished acting career including the best-known lead in the Broadway production of the play Phantom of the Opera.

|

warlover.jpg |

Buzz Job |

All Three B-17s |

The Body |

N5229V on the ramp |

The airplane star of the movie was The Body |

| comment | share |

| Alan Berg | 18-Apr-2021 19:27 | |

| emil dansker | 07-May-2017 20:05 | |

| emil dansker | 07-May-2017 20:03 | |

| emil dansker | 07-May-2017 19:59 | |

| Phil C. Hawkins | 24-May-2016 15:46 | |

| Nigel C. Luther | 13-Mar-2016 15:21 | |

| Guest | 11-Mar-2015 10:34 | |

| Craig R. Covner | 03-Oct-2014 07:21 | |

| Max Hugoson | 28-Jun-2013 22:37 | |

| Max Hugoson | 28-Jun-2013 22:37 | |

| virgi nia maria | 11-Jun-2013 00:07 | |

| virgi nia maria | 11-Jun-2013 00:04 | |

| Guest | 23-Apr-2013 01:06 | |

| Berit Mason | 05-Feb-2013 21:41 | |

| Berit Mason | 05-Feb-2013 21:40 | |

| Terri | 10-Nov-2012 18:05 | |

| Cueburner | 26-Jun-2012 19:52 | |

| Bill Schneider | 21-Apr-2012 22:29 | |

| Mrs Billy Ray Cook Jr | 08-Nov-2011 23:02 | |

| John H.(Lucky) Luckadoo | 24-Oct-2011 22:47 | |

| Guest | 09-Oct-2011 16:54 | |

| Tom Briggs | 21-Aug-2010 14:46 | |

| David E. A. Riker | 14-Apr-2010 22:11 | |

| Jim Walsh | 13-Apr-2010 22:07 | |

| Larry Hopkins | 13-Apr-2010 20:30 | |

| Rory Trappe | 27-Dec-2009 14:00 | |

| Long Bach Nguyen | 21-Dec-2009 16:57 | |